April 1945. somewhere near the Rhine River.

The mud was the first thing you noticed. It wasn’t just dirt and water; it was a slurry of melted snow, churned earth, and the refuse of a collapsing empire. It sucked at the boots of the 32nd Medical Detachment as they disembarked from the deuce-and-a-half trucks, grumbling under the weight of their kits.

Sergeant John Harris adjusted the helmet strap on his chin, squinting through the gray drizzle. He was twenty-six, but the war had carved lines into his face that belonged on a man of fifty. He was a boy from Iowa cornfields who had seen the frozen hell of Bastogne and the hedgerows of France. He thought he had seen everything.

He was wrong.

“Alright, listen up!” Harris barked, his voice rasping over the sound of rain and distant artillery. “We’re setting up triage in the north sector. Intelligence says we’ve got a holding pen full of dysentery, typhus, and malnutrition. Mask up.”

Corporal “Smitty” Smith, a nineteen-year-old from Brooklyn with a chip on his shoulder the size of Manhattan, spit into the mud. “Who are we patching up, Sarge? More SS? I say let ’em rot. Saves us the morphine.”

Harris looked at the boy. Smitty had lost his brother in the Huertgen Forest. The hate was fresh. “We patch up whoever is breathing, Smitty. That’s the job. Now move.”

They trudged toward the barbed wire enclosure. This wasn’t a standard POW camp for combat troops. It was a holding area for the Wehrmachthelferinnen—the female auxiliaries. Secretaries, radio operators, nurses, and administrators who had been swept up in the Allied advance.

When the Americans passed through the gate, the smell hit them like a physical blow. It was the scent of unwashed bodies, sickness, and fear.

Hundreds of women were huddled under makeshift tarps or lying in the open mud. Their gray uniforms were in tatters. Some wore the insignia of the Luftwaffe auxiliary; others were simply civilians caught in the gears of the war machine. They were gaunt, their eyes hollowed out by starvation.

But it was the silence that unnerved Harris. They didn’t scream. They didn’t beg. They watched the Americans with terrified, feral eyes. Goebbels’ propaganda had told them for years that the Americans were gangsters, monsters who would defile and murder them. They were waiting for the end.

“Jesus,” Smitty whispered, the bravado draining out of him. “Look at them.”

Harris walked toward a group of women huddled near a fence post. One of them, a blonde woman whose face was smeared with grime, tried to stand to protect a younger girl behind her. She wobbled, her legs giving out, and collapsed into the muck.

Harris rushed forward, instinctively reaching for his medical bag.

The woman flinched violently, throwing her hands up to shield her face. She let out a sharp, guttural cry, expecting a blow.

Harris froze. He held his hands up, palms open. “Easy,” he said softly. “Easy.”

He looked around. His men were standing back, unsure. They were soldiers, trained to fight men with guns. They weren’t prepared for this—a field of broken women who looked more like ghosts than enemies.

Disgust rippled through the unit—not at the women, but at the situation. It was easier to kill a Nazi soldier than to witness the total degradation of a human being. Some of the medics looked ready to turn around, unable to reconcile the enemy they hated with the skeletons before them.

Harris knew that if he didn’t act now, they would lose the unit’s discipline. More importantly, these women would die.

He stood up, his boots sinking into the slime, and turned to his platoon. His voice didn’t boom; it cut through the rain with the absolute authority of a man who knows what is right.

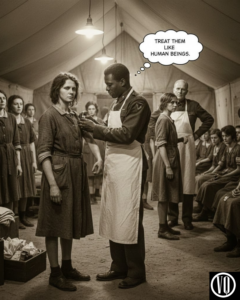

“Listen to me!” Harris shouted.

The medics looked at him.

“I don’t care what uniforms they’re wearing,” Harris said, pointing a finger at the ground. “I don’t care what you think they did or didn’t do. Right now, they are patients. They are sick, they are starving, and they are terrified.”

He looked Smitty dead in the eye.

“Treat them like human beings,” Harris ordered. “That is a direct order. You treat them like they are your sisters, your mothers, or your neighbors back home. We are Americans. We don’t kick people when they’re down. We pick them up. Now get to work!”

The order hung in the damp air. Treat them like human beings.

It was simple. It was profound. It was the one thing the war had tried to beat out of everyone for six years.

Smitty hesitated, looking at the woman on the ground. He took a deep breath, clenched his jaw, and stepped forward. He knelt beside Harris.

“I got the IVs, Sarge,” Smitty grunted.

Helga Fischer thought she was hallucinating.

The fever from the typhus came in waves, turning the gray sky into a kaleidoscope of pain. She was twenty-two years old. Before the war, she had been a music student in Dresden. Then came the draft, the radio operation center, the retreat, and finally, the cage.

She lay in the mud, shivering violently. She watched the American sergeant kneeling over her. She saw the red cross on his helmet. She waited for the cruelty. She waited to be dragged away.

Instead, she felt something warm.

The American was wrapping a wool blanket around her shoulders. He wasn’t rough. His hands were calloused, but his touch was gentle. He was saying something in English—a language she barely understood—but the tone was soft.

He uncorked a canteen and held it to her lips. Clean water.

Helga drank greedily, choking slightly. The sergeant steadied her head. He took a cloth and wiped the mud from her forehead.

Why? she thought. We are the enemy.

Across the camp, a transformation was taking place. The American medics, spurred by Harris’s command, had mobilized. They set up a field kitchen. They erected tents. They moved with the efficiency of an assembly line, but with the tenderness of a hospital ward.

Smitty was cleaning the infected wound on a young woman’s leg. She was crying, shaking with fear.

“Hey, cut it out,” Smitty muttered, though his voice lacked its usual bite. He reached into his pocket and pulled out a Hershey bar—gold in this part of the world. He cracked it in half and handed it to her. “Eat. It’ll help.”

The woman stared at the chocolate, then at Smitty. She took it with trembling fingers.

“Danke,” she whispered.

“Yeah, yeah. Don’t mention it,” Smitty grumbled, wrapping the gauze.

For Harris, the next forty-eight hours were a blur of sleepless exertion. He moved from patient to patient, diagnosing, treating, comforting. He fought the typhus outbreak with sulfa drugs and hygiene.

On the second night, he sat by a small fire they had built near the medical tent. Helga was sitting nearby, wrapped in the blanket he had given her. Her fever had broken.

She looked at him. “Why?” she asked. Her English was broken, but clear.

Harris looked up from his K-rations. He looked at this woman, stripped of her ideology, her country, and her pride, leaving only a frightened human underneath.

“Why what?” Harris asked.

“You… you win,” Helga said. “We lose. You are supposed to… hate.”

Harris took a drag from his cigarette and exhaled a plume of smoke into the cold night. He thought about Iowa. He thought about his mother, who taught Sunday school. He thought about the guys he’d lost.

“Hating is easy,” Harris said quietly. “I’m tired of easy. And I’m tired of death.”

He offered her a cigarette. She took it.

“My name is John,” he said.

She hesitated, looking at the flame of his lighter illuminating his tired face. “Helga.”

“Nice to meet you, Helga.”

It was a small thing. A conversation. A name. But in that mud-soaked pen, it was a revolution.

The dynamic of the camp shifted. The women, initially terrified, realized that these men were not the monsters of Nazi propaganda. They were just men. Men who missed their homes, men who cracked bad jokes, men who were trying to save their lives.

The women began to help. Those who were strong enough volunteered to assist the medics. They boiled water, washed bandages, and translated for the Americans. The barrier of “Us vs. Them” dissolved into “Us vs. Death.”

One afternoon, Smitty was struggling to communicate with a woman who had a severe cough. He was getting frustrated, waving his hands. A woman named Greta, a former clerk, stepped in. She translated Smitty’s instructions, then looked at the Corporal.

“She says you have… kind eyes,” Greta translated, suppressing a small smile.

Smitty turned beet red. “Tell her to just take the damn pills,” he stammered, but he smiled back.

The end of the war in Europe came a few weeks later. The news spread through the camp not with cheers, but with a quiet, heavy relief. The Third Reich was gone. The world was broken, but it was no longer burning.

Orders came down to transfer the prisoners to a permanent processing facility in the rear. The trucks arrived—the same trucks that had brought the medics.

Harris stood by the gate as the women loaded up. They looked different now. They were still thin, still wearing tattered clothes, but they were clean. Their wounds were bandaged. But more than that, they walked with their heads up.

They had been given back their dignity.

Helga was the last to board the truck. She stopped in front of Harris. She looked at the American medic, the man who had seen her at her lowest and chosen to reach out a hand instead of a boot.

“I will never forget,” she said. “I will tell my children. I will tell them that when the world went dark, the Americans brought the light.”

Harris nodded, feeling a lump in his throat. “Take care of yourself, Helga. Go home.”

“You too, John.”

She climbed into the truck. As the convoy pulled away, churning up the drying mud, Harris watched them go.

Smitty walked up beside him, lighting a cigarette. “Well, Sarge. We did it. We kept ’em alive.”

“Yeah,” Harris said. “We did.”

“You know,” Smitty said, scratching his neck. “They weren’t so bad. For krauts.”

Harris smiled. “They were just people, Smitty. Just people.”

Epilogue: 1985

The banquet hall in Berlin was filled with the low hum of conversation. It was a reunion of survivors, a gathering of those who had made it through the chaos of 1945.

John Harris, now sixty-six, his hair white and his back slightly bent, adjusted his tie. He felt out of place. He had returned to Germany for a vacation with his wife, and on a whim, he had answered an invitation he saw in a veteran’s newsletter.

A woman approached him. She was elegant, elderly, leaning on a cane, but her eyes were sharp and blue. She was surrounded by a younger generation—sons, daughters, grandchildren.

She stopped in front of him. She looked at his name tag.

“John,” she whispered.

Harris squinted. The years peeled away. He saw the mud. He saw the blanket.

“Helga?”

She dropped her cane and embraced him. It was a hug forty years in the making. The room went silent as the old American medic and the former German prisoner held onto each other.

She pulled back, tears streaming down her face. She turned to her family—a group of twenty people, successful professionals, happy children.

“This,” Helga said to her family, pointing at Harris. “This is the man. He is the reason I am here. He is the reason you are here.”

She looked at Harris. “Do you remember? You told them to treat us like human beings.”

Harris smiled, his eyes misty. “It was the only order I ever gave that really mattered.”

Helga took his hand. “You did more than that, John. You didn’t just save our lives. You saved our souls. You taught us that even after we had been part of something terrible, we were still worth saving.”

Harris looked at the generations of people standing before him—lives that existed only because a group of tired, muddy American medics had decided to choose compassion over revenge.

He realized then that the war didn’t end with a treaty signed in a schoolhouse. It ended there, in the mud, when fear was replaced by a cup of water and a kind word.

“I was just doing my job, Helga,” Harris said softly.

“No,” she corrected him. “You were being a human being.”

And in a world that had seen too much inhumanity, that was the greatest victory of all.