Part 1: The Stench of Shame and the Million-Dollar Secret

My name is Ethan Miller. I’m the son of a garbage collector. And for twelve years, in the pristine hallways of Westwood High—the wealthiest, most prestigious school in Orange County, California—that fact was my scarlet letter, my daily crucifixion.

While the other kids were flaunting their new Tesla Model S and snapping photos of their catered birthday parties at Disneyland’s Club 33, I was praying for rain to cover the smell that clung to me like a shroud. I didn’t get a new iPhone 17 Pro; I inherited a battered, archaic flip phone my mother found in a dumpster behind a Starbucks in Newport Beach. Every morning, before the sun dared to rise over the Pacific Coast Highway, my mother, Maria, a woman with hands permanently stained and scarred by industrial waste and broken glass, would leave our cramped, single-room apartment in a forgotten corner of Santa Ana. She wasn’t an executive; she wasn’t a doctor. She was a scavenger. She hauled a colossal, industrial-grade canvas bag—a monstrous sack of discarded shame—to the overflowing municipal recycling docks near the LA Port, hunting for enough aluminum cans and plastic bottles to pay the monthly rent of $750.

I didn’t have a childhood; I had an education in survival. While the Westwood kids were discussing their spring break ski trips to Aspen, I was calculating the weight of a hundred plastic water bottles versus a pound of copper wire to see if we could afford a can of SpaghettiOs for dinner. The world saw a boy with threadbare clothes and perpetual dark circles under his eyes. They didn’t see the million-dollar secret I guarded: the fierce, unyielding dignity of the woman whose back was breaking just so I could sit in their air-conditioned classrooms. They didn’t see the raw, explosive truth of sacrifice. They just saw the dirt. They only smelled the trash. And they laughed. It was a brutal, unrelenting mockery that would fuel my revenge.

Part 2: The Hallway Gauntlet and the Public Execution

The first time it happened, I was six years old, standing in the lunch line holding my free, government-subsidized carton of milk. Chad Worthington III, the undisputed King of the Westwood playground—whose family literally owned half of the shopping district in Laguna Beach—pointed a perfectly manicured finger at me and screamed:

“Ew! Did you step in something? Wait—NO! It’s the Trash Kid! The Stench Monster from Santa Ana! Your mommy digs through my family’s garbage! HA! Go back to the dumpster, Miller!”

The entire cafeteria—a sea of designer hoodies and expensive sneakers—erupted in a vicious, high-pitched chorus of laughter. The sheer, naked cruelty hit me like a physical blow. I dropped my milk carton. It exploded on the immaculate tiled floor, the white liquid spreading like a map of my public humiliation. That day, Chad didn’t just call me a name; he performed a public execution of my soul. From then on, the nickname stuck, a brand burned into my identity: The Trash Kid.

Twelve years of this. Twelve years of eating alone in the library during lunch, of being deliberately tripped in the stairwell, of seeing my textbooks smeared with ketchup. No one ever chose me for a group project unless the teacher forced them to. Girls recoiled if I accidentally brushed past them. Even the counselors looked at me with a mixture of pity and revulsion, as if I were a charity case that had somehow managed to breach the perimeter of their perfect, gilded lives. I never fought back. I never yelled. I just absorbed the hate, refined it, and poured it into my grades.

While they were wasting their privilege—binge-watching TV, playing video games, and crashing their luxury cars—I was in the library until closing, soaking up knowledge like a sponge. I didn’t have money for the $150 AP study guides. So, I typed out every chapter by hand on the library’s ancient computer and memorized it. I walked the four-mile journey home every day to save the $2.75 bus fare, and I used that money to buy a single, precious highlighter. Every insult was a new line in my personal manifesto. Every sneer was a promise. A promise that I would not just succeed, but I would shatter their worldviews with the force of my achievement.

Part 3: The Day of Reckoning

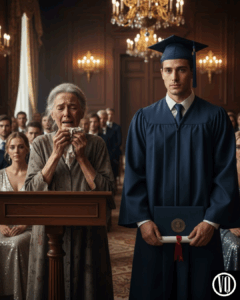

And then, the day arrived: Graduation Day, Westwood High Class of 2025.

The ceremony was held in the massive, state-of-the-art stadium, a structure built with enough donor money to fund a small country. Thousands of people were there: parents in bespoke suits, students preening for their Instagram stories. The air was thick with the scent of expensive perfume, freshly cut grass, and privilege.

As I took my seat in the front row—a visible symbol of my unwanted success—I heard the familiar whispers:

“Look, it’s Miller. The Trash Kid. How did he even manage an acceptance to Stanford? Must have been the pity vote.”

“I heard his mom is literally here. She’s probably sitting in the cheap seats. I hope she didn’t touch anything.”

I glanced toward the back row. There she was. Maria Miller. She was wearing the only dress she owned that wasn’t covered in holes—a faded, floral number that had probably been in a donation box. Her hands, rough and calloused, clutched a small, worn purse. She was a solitary island in a sea of immaculate wealth. But when her eyes met mine, she didn’t just smile; she radiated a pride so blinding it could have melted the gold plating off the principal’s lectern.

Finally, the moment arrived. The principal, Mr. Harrison, stepped up to the microphone, his voice booming over the sound system.

“And now, for the highest honor, the Valedictorian of the Westwood High Class of 2025, who graduates with a perfect 4.0 GPA and an acceptance to the prestigious Stanford University… Mr. Ethan Miller!”

A stunned silence. The applause was polite, hesitant. They were applauding the achievement, not the person. I rose, my legs feeling like lead, and walked up the steps toward the stage. I was handed the gleaming gold Valedictorian medal. It was heavy. It was real. It was twelve years of discarded aluminum and broken bottles forged into a single, shining prize.

When I reached the podium and the applause finally died down, the silence was absolute. The entire stadium—all 5,000 people—was waiting for the Trash Kid to deliver his predictable, humble speech about hard work and opportunity.

I adjusted the microphone. I looked directly into the camera, knowing this was being livestreamed across the state. Then, I bypassed the script.

Part 4: The Mic Drop Heard ‘Round the County

“Thank you, Principal Harrison, esteemed faculty, and the parents who made sure their children never had to worry about rent or dinner,” I began, my voice steady, but with a low, controlled intensity.

“For the past twelve years, I have been known by many names in these hallways. My favorite was ‘The Trash Kid.’ And that is what I want to talk about today.”

A collective gasp swept through the crowd. I saw Chad Worthington III, now sitting smugly with his parents, suddenly lean forward, his smugness replaced by confusion.

“For years, you’ve judged me by the smell of the Santa Ana bus, or the holes in my shoes, or the fact that my mother, Maria Miller, works as a recycler—a garbage collector. Some of you have whispered that I don’t belong here, that my success is a fluke, a burden on your wealthy environment.”

I paused, letting the words sink in, watching the faces of the privileged parents turn from bored indifference to horrified realization.

“Let me be clear. I am here because of the trash. I am here because of the stench. I am here because of my mother’s hands, which are scarred not from manicures, but from broken glass and rusty metal—the trash that your families threw away.”

I took a deep breath, and this was the pivot. The phrase I had rehearsed every night. The phrase that contained the full, concentrated force of my revenge and my love.

“The reason I stand here today, the Valedictorian heading to Stanford, is simple: Every single one of my accomplishments—every A, every scholarship, every perfect test score—was paid for by something my mother pulled out of your family’s garbage can.”

The stadium was stone silent. You could hear the clicking of my mother’s old, cracked-screen flip phone as she tried to take a picture from the back row.

“You see,” I continued, my voice now rising with undeniable passion, “while your parents bought you tutors, my mother bought me time. While your parents bought you Tesla cars, my mother bought me the freedom to dream by ensuring we didn’t starve. She taught me that the real trash isn’t plastic, it’s a person who judges the worth of another human being based on their bank account.”

I looked down at the gleaming medal. “This medal? It doesn’t belong to me. It belongs to the woman who showed me that dignity is not found in what you buy, but in what you are willing to do for love.“

I slowly, deliberately, unhooked the medal from around my neck. The gold shone blindingly under the stadium lights. I turned and walked straight to the edge of the stage. The entire school watched, frozen. I didn’t look at the faculty; I didn’t look at the Worthington family.

I looked at my mother, Maria Miller, sitting alone in the back row.

Part 5: The Unstoppable Wave of Truth

I held the microphone close again. “My final act as a student of Westwood High is to return this medal to its rightful owner. Because she is the real hero of this story.”

Then, I did the unthinkable. I jumped down from the stage—a six-foot drop—and ran, sprinting past the front rows of shocked parents and faculty. The crowd parted as I ran down the aisle, my black graduation gown flying behind me.

I reached the back row where my mother sat, tears streaming silently down her face. I didn’t say a word. I knelt on the concrete floor, reverently, like a knight before his queen, and placed the Valedictorian medal around her neck.

“Mamá,” I whispered, my voice breaking for the first time. “It’s yours. You earned it. You are the most dignified woman in this entire county.”

She pulled me up and held me in a crushing embrace.

That was the breaking point. The thousands of silent people—the parents, the teachers, the students—could no longer hold it in.

The first sound was a muffled sob from one of the teachers. Then, a raw, choking cry from a father who suddenly realized the depth of his own entitlement. Then, a massive, unstoppable wave of emotion swept through the stadium. Everyone was crying. Not for me, but for the devastating, pure truth of my mother’s sacrifice and the shame of their own past judgments.

My former tormentors, Chad Worthington III and his cronies, rushed toward me. They didn’t sneer; they didn’t laugh.

“Ethan… Ethan, I’m so sorry,” Chad mumbled, his face pale and wet with tears. “I was an idiot. We were all wrong. I didn’t see… I didn’t see her.“

I looked at him, no longer with hate, but with an immense, quiet pity. “You were just spoiled, Chad. The world is bigger than your trust fund. Just promise me one thing: the next time you see a recycling collector, look her in the eye. See the dignity.”

He nodded, unable to speak, and stepped back.

Part 6: The Richest Woman in Orange County

The ceremony ended with a standing ovation, not for the graduates, but for the woman in the faded floral dress wearing a gleaming gold medal. Maria Miller, the Garbage Collector, was the true Valedictorian.

After the pandemonium subsided, my mother and I stood alone for a moment outside the stadium, bathed in the gentle California sunlight.

“Hijo,” she said, her voice husky, touching the medal. “You don’t need to do this. You are going to Stanford. You are free now.”

I smiled, a genuine, untroubled smile for the first time in years. “I’m not free from you, Mamá. I’m free because of you. And the moment I became Valedictorian was the moment I got to tell the world who my hero is. The debt is paid.”

I got a full-ride scholarship to Stanford, of course. But before I left for Palo Alto, I used my part-time job savings to buy my mother a small, used van—not for her to collect trash, but for her to start her own small, legitimate, and ethical recycling business. She still worked hard, but now she worked with respect, and for herself.

My mother never became rich in the way the Worthingtons defined it. She never lived in a mansion in Malibu. But that day, kneeling before her with a gold medal, I realized the full, breathtaking extent of our wealth.

The person who is truly rich is not the one who has never touched dirt, but the one whose heart is so full of dignity and love that it can cleanse the dirt from the entire world.

And in that moment, standing on the sidewalk of the most exclusive high school in America, looking at the proud, tear-stained face of my mother, Maria Miller, the former Trash Kid knew one thing: We were the richest family in Orange County.