The rain in the Pacific Northwest doesn’t just fall; it invades. It soaks into the timber, turns the logging roads into rivers of slurry, and rusts anything made of iron that sits still for more than a day.

Theodore Alfred “Al” Peterman stood in the mud of his logging camp, water dripping from the brim of his fedora. He wasn’t looking at the towering Douglas firs that made him one of the wealthiest plywood magnates on the West Coast. He was looking at a truck.

Or rather, what used to be a truck.

It was a standard-issue hauler, built in Detroit by engineers who thought “rough terrain” meant a cobblestone street. The rear axle had snapped clean in half, leaving the massive load of logs listing dangerously to the left. The transmission casing was cracked. The frame was twisted.

“That’s the third one this month, Mr. Peterman,” his foreman shouted over the driving rain. “These rigs just can’t take the weight. The grades are too steep, the mud’s too deep.”

Peterman wiped rain from his face. He was a man of solutions, not excuses. He had built his empire by solving problems—finding better ways to peel veneer, better ways to cure plywood. But this? This was costing him money. Every broken axle meant downtime. Every day logs sat in the forest, mills sat idle.

“Fix it,” Peterman growled.

“With what?” the foreman asked, exasperated. “We can buy another White or a Mack, but they’ll just break too. Nobody builds a truck for this.”

Peterman looked at the broken machine. He looked at the unforgiving landscape. And then, a thought struck him—a thought that would change the American highway forever.

If nobody builds a truck for this, then I will.

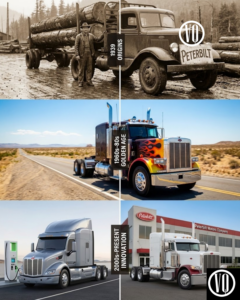

The Resurrection Oakland, California, January 1939

Fageol Motors was dying. Once a pioneer in the industry, the Great Depression had bled it dry. The factory in Oakland was silent, the machines cold, the workers laid off.

Al Peterman walked through the empty facility, his footsteps echoing on the concrete floor. He wasn’t an engineer. He wasn’t a mechanic. But he knew what he needed.

He sat down in the dusty office of the receivership attorneys and pulled out his checkbook.

“You’re buying the whole thing?” the attorney asked, incredulous. “The patents, the tooling, the inventory?”

“Everything,” Peterman said. “Except the name. The name stays here.”

He signed the check. It was a massive gamble. He was taking his timber fortune and betting it on a dead truck company.

He gathered the remaining engineers—men who were hungry, talented, and desperate for work. He laid out his vision on a drafting table covered in coffee stains.

“I don’t want a highway truck,” Peterman told them. “I want a tank that hauls logs. I want frame rails twice as thick as standard. I want axles that can handle double the load rating. I want a transmission that can climb a vertical wall.”

The engineers looked at each other. “Mr. Peterman, that will make the truck heavy. And expensive. Nobody will buy it.”

“I’ll buy it,” Peterman said. “And if it works, every logger from here to the Yukon will buy it too.”

They went to work. They stripped the old Fageol designs down to the bolts. They reinforced stress points. They swapped out light-duty parts for heavy-duty iron. They hand-built the cabs from steel, welding and riveting them until they were solid enough to take a falling branch without crumpling.

In late 1939, the first truck rolled out of the Oakland factory. It bore a new name on the radiator grille, a red oval script that combined Peterman’s name with the act of creation.

Peterbilt.

The War Machine 1941-1945

The first Peterbilts were monsters. They were overbuilt, heavy, and practically indestructible. Loggers in Oregon and Washington bought them cautiously at first, then enthusiastically. A Peterbilt didn’t break. It just kept pulling.

But the real test came on December 7, 1941.

When the bombs fell on Pearl Harbor, America woke up. The War Department needed trucks—thousands of them. They needed vehicles that could haul tanks, bridge sections, and massive loads of timber for constructing bases in the Pacific.

General Motors and Mack got the big contracts for standard troop transports. They had the assembly lines. But for the heavy lifting? For the jobs that required brute strength? The Army came to Peterbilt.

“We need a truck that can haul a Sherman tank through a swamp,” an Army colonel told Peterman.

“We can do that,” Peterman said.

The war forced Peterbilt to evolve. They couldn’t just hand-build every truck like a bespoke suit anymore. They had to learn volume. They standardized parts. They streamlined the assembly line. But they refused to compromise on the core philosophy: overbuild everything.

By 1945, Peterbilt trucks were hauling heavy equipment across Europe and the Pacific. GIs marveled at them. They were the iron horses of the engineering corps.

When the war ended, Peterbilt wasn’t just a niche logging truck company anymore. It was a legend.

The Golden Age of Chrome 1958-1980

Al Peterman died in 1944, never seeing the full scope of his legacy. His wife sold the company to a group of managers, but by 1958, Peterbilt needed capital to grow.

Enter PACCAR—Pacific Car and Foundry. They already owned Kenworth, another heavy-duty truck manufacturer. Industry analysts predicted PACCAR would merge the two brands, creating a generic “Kenny-Pete” truck.

PACCAR was smarter than that. They understood brand loyalty. They kept Peterbilt separate, giving them the funding to innovate while maintaining their distinct culture.

And innovate they did.

In 1967, Peterbilt launched the Model 359.

It wasn’t just a truck. It was a statement.

It had a long, square hood made of lightweight aluminum. It had a vertical grille that looked like the portcullis of a castle. It had massive, dual exhaust stacks that roared like dragons.

The 359 hit the market just as the culture of the American “Owner-Operator” was exploding. Truckers weren’t just employees anymore; they were independent businessmen, cowboys of the asphalt. They wanted a truck that reflected their pride.

The 359 became the icon of the American highway. It was customized with acres of chrome, chicken lights, and custom paint jobs. It starred in movies. It was the hero of country songs.

“If you ain’t driving a Pete, you ain’t driving,” became the slogan of truck stops from Texas to Maine.

But beneath the chrome, it was still Al Peterman’s logging truck. The frame rails were still thicker. The suspension was still heavy-duty. A Peterbilt 359 could run a million miles, get rebuilt, and run a million more. It held its value better than gold.

The Modern Era 2000-Present

The 21st century brought new challenges. The EPA cracked down on diesel emissions. Fuel prices skyrocketed. The industry shifted toward aerodynamics and efficiency.

Competitors like Freightliner and Volvo introduced “jellybean” trucks—rounded, smooth, plastic-heavy designs that slipped through the wind but looked like appliances.

Peterbilt faced a crisis. How do you maintain the tough, classic image while meeting modern standards?

They threaded the needle.

In 2007, they retired the legendary 379 (the successor to the 359) and introduced the Model 389. It kept the long hood, the external air cleaners, the classic look. It was a defiant middle finger to the aerodynamic trend, built for the purists who demanded style and tradition.

But they also launched the Model 579—a sleek, aerodynamic truck designed for fleets. It proved that Peterbilt could do high-tech efficiency without losing its soul.

Today, Peterbilt is a dichotomy.

On one side, you have the 589 (the newest classic), beloved by owner-operators who polish their aluminum tanks every weekend. On the other, you have the 579EV, an electric truck running silently through city streets, and SuperTruck II, a futuristic prototype that gets double the fuel mileage of a standard rig.

But walk onto the assembly line in Denton, Texas, and you’ll still see the ghost of Al Peterman. You’ll see frame rails with the C-channel facing down for extra strength. You’ll see steel cabs being riveted together. You’ll see workers who take immense pride in building “Class.”

The Legacy

Eighty-five years ago, Al Peterman stood in the rain and decided that “good enough” wasn’t good enough. He didn’t just build a better truck; he built an identity.

Today, Peterbilt isn’t just a brand. It’s a culture. It represents the American spirit of independence, grit, and the refusal to compromise.

When you see a long-nose Peterbilt hammering down the left lane of the interstate, chrome gleaming in the sun, diesel smoke puffing from the stacks, you aren’t just seeing a vehicle. You’re seeing a direct lineage to the muddy forests of the Pacific Northwest, where one man decided to conquer the elements with iron and will.

Al Peterman’s trucks didn’t just haul logs. They hauled the American Dream.