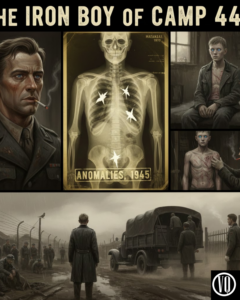

I. The Impossible X-Ray

The skeleton glowing against the backlight of the medical tent shouldn’t have been walking. It shouldn’t have been breathing, let alone standing at attention in the mud outside.

Captain Elias Thorne, a surgeon from Chicago who had spent the last two years stitching men back together from Omaha Beach to the Rhine, took a long drag of his Lucky Strike. He narrowed his eyes at the film clipped to the lightbox. The hum of the generator outside was the only sound in the cramped radiology tent, save for the rhythmic drumming of rain against the canvas.

“You’re seeing what I’m seeing, right, Cap?” the radiology tech, Corporal Miller, asked. His voice was tight, wavering somewhere between fear and confusion.

Thorne didn’t answer immediately. He stepped closer, the smoke curling around his fingers.

There were five of them. Five jagged, irregular shapes explicitly rendered in white against the ghost-grey shadows of ribs and muscle.

One was lodged deep in the left thigh, nestled dangerously close to the femoral artery. Another sat like a heavy coin just above the pelvic bone. Two smaller shards were embedded in the right shoulder complex, entangled in the rotator cuff. But the fifth one—that was the one that made Thorne’s stomach turn. It was a jagged splinter of metal, likely steel, resting millimeters from the third lumbar vertebra.

“Is this a intake error?” Thorne asked, his voice gravelly. “Did this kid swallow a toolbox?”

“No, sir,” Miller whispered. “Those are shrapnel. High-velocity fragments. And Cap… look at the bone density around them. Look at the calcification.”

Thorne leaned in, his nose inches from the film. Miller was right. The edges of the metal weren’t sharp against the tissue; they were blurred, encased. The body hadn’t rejected the invaders; it had swallowed them. It had built walls of calcium and scar tissue around the steel, effectively incorporating the shrapnel into the boy’s anatomy.

“These aren’t fresh,” Thorne muttered, the realization chilling him more than the damp European air. “This kid has been carrying a junkyard inside him for months. Maybe years.”

Thorne killed his cigarette in a tin can. “Bring him in. And clear the room. I don’t want the MPs spooking him.”

“He’s not spooked, Cap,” Miller said, looking toward the flap of the tent. “That’s the problem. He’s not anything.”

II. The Ghost in the Grey Uniform

The prisoner was nineteen, but he looked simultaneously like a twelve-year-old and an eighty-year-old.

His name, according to the intake log, was Lukas. No rank. No unit patches remaining. Just a Wehrmacht tunic that was three sizes too big, hanging off his gaunt frame like a shroud. He sat on the edge of the examination table, his boots hovering inches above the floor. They were worn through to the soles, wrapped in rags to keep out the wet.

When Thorne entered, Lukas didn’t flinch. He didn’t jump to attention, nor did he cower. He simply sat there, staring at a spot on the canvas wall with eyes that were a piercing, empty blue. It was the “thousand-yard stare,” a look Thorne had seen on Marines in the Pacific and GIs in the Ardennes. It was the look of a soul that had vacated the premises to let the body survive.

Thorne grabbed a stool and sat opposite the boy. He spoke passable German—enough to ask where it hurt, usually.

“Lukas,” Thorne said softly.

The boy’s eyes flickered to Thorne’s face. Acknowledgment, but zero emotion.

“Do you know what is inside you?” Thorne pointed a thumb toward the X-ray film still glowing in the corner.

Lukas nodded once. Slow. Deliberate.

“Metal,” Thorne said, switching to English, then back to German. “Eisen. Steel. Five pieces.”

Lukas nodded again.

“Does it hurt?”

The boy paused. It was the first time his expression changed—a microscopic furrow of the brow, as if he was trying to remember what pain felt like. “Not anymore,” he said. His voice was rust and gravel, unused.

Thorne stood up and gestured for the boy to remove his tunic. Lukas complied without hesitation. As the wool fell away, Thorne hissed a breath through his teeth.

The boy’s torso was a roadmap of violence. It wasn’t just the entry wounds for the metal; it was the history of a collapsing nation written on skin. There were burn marks that had healed into shiny, tight patches. There were long, thin white lines from barbed wire or knives. And there were the entry points for the five fragments—puckered, violet depressions that looked like craters on a moon.

There was no sign of surgery. No neat suture lines from a field hospital. These wounds had been bound with dirty rags and willpower.

“Who treated you?” Thorne asked, putting on his gloves to palpate the shoulder. He felt the hard lump of metal under the skin. It moved slightly with the muscle.

“No one,” Lukas said.

Thorne stopped. “No one? You took shrapnel near your spine and you walked it off?”

“We were moving,” Lukas stated simply. “If I stopped, I stayed behind. If I stayed behind…” He trailed off. He didn’t need to finish the sentence. On the Eastern Front, or during the chaotic retreat from France, being left behind meant death.

III. The Camp Whisperer

By the next morning, the story of the “Iron Boy” had bled out of the medical tent and into the general population of Camp 44.

A prisoner-of-war camp is a hive of boredom and rumor. Secrets are the only currency that matters. The story of Lukas morphed as it traveled from the latrines to the chow lines. Some claimed he was a Nazi super-soldier experiment, impervious to bullets. Others whispered he was cursed, a golem made of mud and steel that couldn’t die because hell didn’t want him yet.

The American guards, usually loud and brash, gave Lukas a wide berth. There is something deeply unsettling to the human mind about an anomaly. We understand blood; we understand death. We do not understand a boy who walks around with enough shrapnel in his gut to kill a mule, eating his watery soup as if nothing is wrong.

Thorne watched him from the window of his office. Lukas was in the yard, standing in the rain. Other prisoners huddled together for warmth or traded cigarettes. Lukas stood alone.

“He’s terrifying them,” Major Halloway, the camp commander, said, standing beside Thorne. “The other Krauts. They think he’s a bad omen.”

“He’s a medical miracle, Major,” Thorne corrected. “Or a biological tragedy. I’m not sure which.”

“Can you operate?” Halloway asked. “Get that junk out of him? Maybe he’ll start acting human again.”

“I could,” Thorne said, rubbing his tired eyes. “The one near the spine is tricky, but the others… yeah, I could dig them out. But I’m not sure I should.”

“Why the hell not?”

“Because,” Thorne watched as Lukas slowly turned his head to watch a bird land on the barbed wire fence. “I think the metal is the only thing holding him together.”

IV. The Interview

Thorne brought Lukas back in three days later. The boy looked slightly better—the regular rations were putting a little color back into his cheeks—but the silence remained.

Thorne had brought in a psychologist, Lieutenant Evans, to sit in. Evans was a fresh-faced academic from Yale who thought everything could be solved by talking about one’s mother.

“Ask him why he didn’t surrender sooner,” Evans whispered. “Ask him why he didn’t seek medical help when the lines crossed.”

Thorne translated the question. “Lukas, why didn’t you go to a hospital? Why didn’t you tell the Americans at the first checkpoint that you were wounded?”

Lukas looked at his hands. They were calloused, the fingernails black with dirt that scrubbers couldn’t reach.

“The hospitals were full,” Lukas said softy. “They were for the men who were screaming.”

“You were in pain,” Thorne pressed. “You had metal tearing your muscle.”

Lukas shrugged. It was a small, devastating motion. “Others had it worse.”

Thorne felt a heavy weight settle in his chest. Others had it worse. It was the mantra of a generation of children who had been fed into the meat grinder of total war. This boy had been taught that his individual existence was meaningless compared to the collective struggle, and then, when the struggle collapsed into chaos, he learned that his pain was irrelevant compared to the screaming men dying in the mud beside him.

“Tell me about the metal,” Thorne said, changing tactics. “Do you remember when each piece went in?”

For the first time, Lukas’s eyes glossed over, seeing something far beyond the tent walls.

“The leg… Kharkov. Artillery,” he murmured. “The shoulder… a building fell. Near Dresden. The back…” He touched his lower spine unconsciously. “I don’t know. I woke up in a crater. It was there.”

“You woke up in a crater and kept walking?” Evans asked, incredulous.

“Everyone was walking,” Lukas said. “To stop is to die.”

V. The Ethical Blade

The dilemma kept Thorne awake for two nights.

Medically, the fragments posed a risk. Lead poisoning, migration of the metal into an organ, late-stage infection. The Hippocratic Oath suggested he should intervene. He had the scalpel; he had the penicillin. He could make the boy “clean.”

But as Thorne watched Lukas navigate the camp, he realized the adaptation wasn’t just physical. The boy had built a psychological armor around those wounds just as his body had built calcium walls. He was a survivor. To cut him open now, to put him under anesthesia and render him helpless, felt like a violation of the truce the boy had made with death.

Thorne called Lukas in one last time.

“I can take them out,” Thorne said. He had laid the surgical tools out on the tray. The steel gleamed under the electric light. “I can put you to sleep. When you wake up, the metal will be gone. You won’t have to carry it anymore.”

Lukas looked at the instruments. He looked at the X-ray still hanging on the wall—the picture of his own secret architecture.

He reached out and touched his chest, right over where a rib had healed crookedly around a shard.

“No,” Lukas said.

“It might kill you one day,” Thorne warned. “If it moves.”

Lukas looked Thorne in the eye. The blue was less empty now. There was a spark of something—defiance, perhaps, or just profound acceptance.

“It is mine,” Lukas said. “It is… what is left.”

Thorne understood then. The metal wasn’t just debris. It was witness. It was the physical proof that he had survived the fire. If Thorne cut it out, he would be removing the boy’s history, leaving him with nothing but empty scars and the memory of fear.

“Okay,” Thorne whispered, dropping his hands. “Okay, Lukas. We leave it.”

VI. The Departure

The war in Europe ended with signatures on paper, but in the camps, it ended with the opening of gates.

Months later, the processing for repatriation began. Lukas was on the list. He was given a fresh set of civilian clothes—rough wool trousers, a white shirt, a heavy coat.

Thorne stood by the gate as the trucks loaded up. The mud had dried into hard, cracked earth. The sun was actually shining, a rare occurrence that felt almost sarcastic given the devastation of the landscape.

Lukas moved down the line. He didn’t look back at the barracks. He didn’t say goodbye to the other prisoners. But as he reached the tailgate of the Deuce-and-a-Half truck, he stopped.

He saw Thorne.

The doctor and the prisoner locked eyes. There was no salute. No handshake. Those things belonged to a world of order that didn’t apply here.

Lukas gave a single, imperceptible nod. He touched his shoulder, just once—a gesture acknowledging the burden he still carried, and the man who had allowed him to keep it. Then he climbed into the truck.

The engine roared to life, spewing black smoke. As the truck rumbled away, disappearing into the dust of a broken Europe, Thorne lit a cigarette.

“You let him go with the shrapnel?” Corporal Miller asked, stepping up beside him. “That kid is a walking time bomb.”

” aren’t we all, Corporal?” Thorne exhaled a long plume of smoke. “Aren’t we all.”

VII. The Archive

Lukas vanished into the post-war chaos. There were no memoirs written by him. No interviews on the anniversary of D-Day. He returned to a Germany that was rubble and ash, and he rebuilt a life in silence.

Did the metal eventually kill him? Did he live to be eighty, telling his grandchildren that he was made of iron? No one knows.

But in the dusty archives of the U.S. Army Medical Department, filed under “Anomalies, 1945,” the X-ray remains.

The film has yellowed with age, but the white shapes are still stark and bright. Five pieces of jagged steel, floating in the darkness of a human body. They remain a silent testament to a nineteen-year-old boy who walked out of the apocalypse refusing to speak of his pain, simply because he believed that in a world drowning in blood, his own suffering was not worth mentioning.

It serves as a quiet, haunting reminder that while history is written in books, the true cost of war is often carried, hidden and silent, inside the people who survive it.